Queensmere, Slough

Queensmere Shopping Centre, Slough. What becomes of you, my love?

No one takes credit for it. No architect puts their name to it. This concrete shopping centre that it took most of the sixties to build.

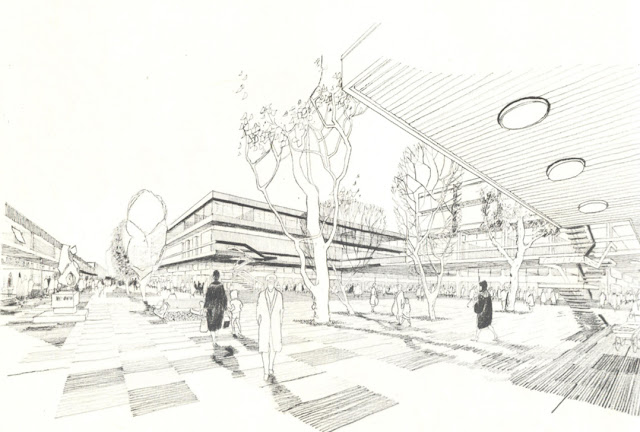

It’s 1958 and town planners have a vision for Slough: shops, squares with fountains, abstract Hepworth-like statues, geometric concrete angles and beautiful trees growing in the cracks. Slough is part of a larger project to clear slums in London and rehouse those living in them to something better. Slums with Londoners still living in bombed out houses - no water, no electricity, no plumbing for decades. It took an Act in the late 60s to cash incentivise landlords to see tenants as humans.

|

| From the Borough of Slough document: "An Approach to Renewal" |

The Greater London Council designs estates in Britwell and Langley (parts of Slough). It’s going to take ten years and in fact it takes to 1973 for Queensmere shopping centre to open.

|

| From the Borough of Slough document: "An Approach to Renewal" |

The walk from Slough train station took you past the concrete stars of the Brunel Bus Station (since demolished) through a concrete walk way under the main road across to the subterranean Queensmere shopping centre entrance. I feared for my pocket change every time I took that underpass as a kid. One of my dad’s fantastical stories recall him walking down these underpasses drunk and knocking two would be muggers out.

In separating out pedestrians and traffic, developers created the wrong kind of corners and edge.

|

| Courtesy of the Slough I Remember Facebook page. |

But I envy to some degree living in a time of reimagining. When most built environments were still bombed out or left to decay, I can imagine the architects, urban planners and politicians of the day sitting in a concrete Mount Olympus planning new town centres and huge housing estates like Zeus and Prometheus modelling clay for their humanity 2.0. Each one deluded that they are Prometheus.

I don’t think that this has ever been better represented than by J.G. Ballard’s Anthony Royal character in the 1975 novel “High Rise”. Living in the community building and sinking with it as its captain. Almost like Goldfinger in Balfron Tower, except he left because his wife realised that living there was shit and no amount of champagne evenings would change that.

|

| Courtesy of the Slough I Remember Facebook page. |

It’s hard to see now that in the sixties and seventies, the brutalist and modernist architecture being assembled around the country under the discipleship of Le Corbusier was a vision of the future. But the future doesn’t age as well as the past. Cities like Oxford, Bath and York will remain beautiful forever, but these cities didn’t offer homes for many outside an elite.

In Oxford there was even an estate that put a Belfast wall in a road between private and social housing.

Growing up in Slough after my parents left a very different version of London than I came to discover twenty years after, I think I am left with this hopeful desire for the future, but a very analogue future. A tactile, physical future of buttons, clunks and clicks, concrete and Bauhaus chairs, computer consoles, floppy disks, mechanisms and an understanding of complexity without everything we own being in the air.

Slough city-centre in the 1980s and 1990s was nothing like it is now, well it was a bit like it was now, but nowhere near as awful. There has always a wariness that we had in navigating it. My trips in to Slough town centre took about half an hour from where I lived and I was only walking in to spend the money that I made from cleaning offices after school on music cassettes. I shared a room with my two brothers and my musical world was still my walkman.

When I was ten or eleven I walked up to the Our Price counter with an NWA album, and they refused to sell it to me, thanks to Tipper Gore and the PMRC. I put the cassette back where I found it and came back with the first Cypress Hill album. “Same problem, kid”. Luckily a HMV opened in Queensmere with a wall of cassettes. It wasn’t a long wall, but I’d scour that selection of cassettes in forensic detail.

This same cassette was always there, and because I couldn’t see anything else I wanted, I bought it. It was the seven songs EP from Fugazi and from the opening bass line of “Waiting Room” I knew that my world was much much bigger. I could see a world outside Slough (that wasn't Compton).

People who grow up in shitty towns have to have the hope of a life beyond that town. And Slough was that hope from those coming from the worst of environments from parts of London that “weren’t fit for humans now”. At least in 90s Slough there were comic book shops, alternative night clubs that would allow my band to play at 15 years old, record shops, and a rehearsal studio that still exists to this day.

Now, I’m visiting and this is a place that doesn’t offer young people anything. As a father of two kids, I’m still trying to catch up with how a virtual world offers this generation what we had, even in the worst of environments.

Notes:

https://www.philipsuter.co.uk/An_Approach_To_Renewal_Slough.htm

This is a great documentary on the fate of estates built in the late 60s/early to mid-70s:

https://youtu.be/xHeUj2HjJek?si=fsSaLeTHFuxLjM9C

Comments

Post a Comment